Almost no one writes about what happens after the victory, the hard work and daily struggle after the barricades, the factory occupations, the mass mobilizations. So I’m rather fascinated by the few that do, especially when they do it both deeply and beautifully.

The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin is much loved and much discussed in certain circles and almost entirely unknown in others, making it hard to know where to start when writing about it. I shall never do it justice, but it is undoubtedly one of the books that changed how I think about the world when I first read it, and that offers up new insights every time I go back.

In brief the planet Urras is as much like Earth during the cold war as an imaginative and richly described future world could be. Some two hundred years before the book’s events, a woman named Odo led an anarcho-syndicalist rebellion on Urras, successful enough to win the moon of Anarres for an anarchist settlement ruled through consensus rather than hierarchical government.

It is bleak and bare, a place demanding that survival be fought for. The people of Anarres change their language and their laws and their relationships, erasing the possessive. You no longer lend or borrow, but you share. You no longer have, instead you use. If you wish to love and hold only one person you may, but they are even less yours than the children. And they succeed in all of these things; they have wrested two hundred years of survival from an unforgiving environment where nothing, absolutely nothing can be wasted. Although limited by this desert to a grimness that no one could aspire to, they build a society of equality, fairness and mutual aid, and one that is arguably far better than anything we can see today.

It is worth reading to explore and think about this society alone.

And yet. The main drama of the book hinges around a scientist, Shevek, whose research seeks to go beyond all that is known. He is held back, discouraged, isolated for seeking to know too much, for crossing society’s unspoken boundaries, for indulging in his ego. And so loving Anarres as he does, he leaves it for Urras. He goes there seeking to help his people, knowing that they will all believe him to have betrayed them. What of science (and writing and all similar things) is ego, and what a joy in your work, a drive to create, a desire to make the world better?

Still, for me the key question remains: how do you build something beautiful and solid, and yet also avoid stagnation? How do you avoid even the simple rules of an anarchist society becoming calcified and limiting? The reality is that utopia truly belongs to its name, no- place. It is something that we must continually build, develop, work towards.

Related to this, and a discussion much on my mind lately, is the way that people grow and transform themselves through struggle, and that this struggle is in fact a necessary part of developing our full capacities. Any system that does not allow for individuals to take risks, engage creatively and create their own sense of ownership, whether it be an organization, a democratic structure, or a utopia itself, is in fact limiting, deforming, oppressive. I intrinsically distrust perfection, and perhaps that is why. There is no way to grow, and there can be nothing new for anyone to contribute.

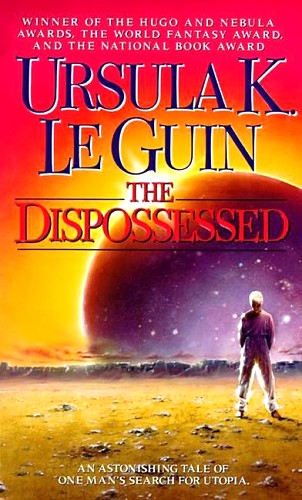

There is so much more here, and indeed in all of Le Guin’s writing. She is one of the very best. So just a final aside as a writer and an editor! I find the different covers of The Dispossessed to be extraordinary, and they show clearly both how readers are segmented into markets, and how certain writers transcend all of those segments. Just look at the covers below, think about the one you might have picked up in the store and the ones you would never, and then think about all the quality literature you just might be missing!

Thanks for sharing that……….

yes it changed my views a bit too, but notice how the scene of happy kiddies romping in the snow, and and a happy home life is Pae’s home on Urras.

For all Pae is judged by Shevek as a evasive, and despised as a “filthy profiteering liar” at one turning point, in the novel, he has something Shevek keeps on walking away from, which their whole society walks away from, a home life.

And yes, peple have “Imagined” a life without greed or war, and this is indeed one attempt.

I do not even know how I stopped up right here, however I thought this publish was great.

I do not understand who you’re however definitely you’re going to a famous blogger in case you aren’t already.

Cheers!