Guest blogger, Susan D. Anderson, is the author of Nostalgia for a Trumpet: Poems of Memory and History, and has written, taught and lectured widely on African American history and politics. She is Curator, Collecting Los Angeles, at UCLA Library. Her literary blog is The Obsessive Reader’s Cultured Ghetto. Susan is currently completing a novel.

As a Californian, I have lived in the shadow of Utopia all my life. My mother’s family arrived from New Orleans on one side; and Louisville on the other. It was at the turn of the 20th century; already the state’s image was of the “Land of Sunshine” – physically, psychically, as well as in the skies. Within the perceived paradise of California, real utopias were being built, Kaweah Colony, Llano del Rios, Halcyon and others. According to historian Robert Hines in California’s Utopian Colonies , “From 1850 to 1950 California witnessed the formation of a larger number of utopian colonies than any other state in the Union. In this period at least seventeen groups embarked on an idealistic community experiment in California.”

As a Californian, I have lived in the shadow of Utopia all my life. My mother’s family arrived from New Orleans on one side; and Louisville on the other. It was at the turn of the 20th century; already the state’s image was of the “Land of Sunshine” – physically, psychically, as well as in the skies. Within the perceived paradise of California, real utopias were being built, Kaweah Colony, Llano del Rios, Halcyon and others. According to historian Robert Hines in California’s Utopian Colonies , “From 1850 to 1950 California witnessed the formation of a larger number of utopian colonies than any other state in the Union. In this period at least seventeen groups embarked on an idealistic community experiment in California.”

One of the least known American utopias is Allensworth, California, an independent black town, established in 1908, forty miles north of Bakersfield, in the great, agricultural San Joaquin Valley. You approach Allensworth today on a road that is desolation itself. The soil is alkaline, unstable, dust puffing into waves above the horizon. At this time of year, the cold is profound. Thick Tule fog has you driving in blindness, it rolls by, shrouds your car. Sounds are muffled by the great stone walls of the Eastern Sierra Mountains. You drive past dead fields and trailer heaps, ramshackle ranch homes on isolated lots. Then, in the distance, tidy small buildings and the incongruous ranger station. You crunch your car to a stop in a gravelly parking lot.

It’s possible to feel overwhelmed when you finally arrive at Allensworth. Especially if you know something of the hidden history of America. The U.S. past is littered with the remnants of thousands of communistic societies; the Utopian enterprise was universal across the states and territories. Americans took their various interpretations of The Promised Land and tried to implement them. Utopianism was constructed out of the deep yearnings of a fugitive, impatient, pragmatic people to inhabit the City of God. Now.

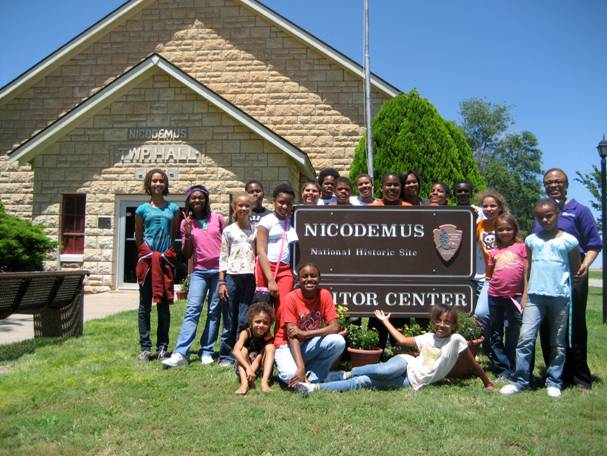

American school children grow up in ignorance of this heritage. Even less is known about the independent black town movement, starting in 1830 with the establishment of Brooklyn, Illinois and continuing through the 1910 founding of Dearfield, Colorado . Search the entire literature of Utopia, and you will not find the American black town movement, nor any of the individual towns. Many of these settlements were established after Reconstruction, as black people left the South in droves, when the federal government withdrew troops in 1877, and in the vacuum rose the Ku Klux Klan, Black Codes, and lynchings. The migration was so massive that the U.S. Senate spent three months holding hearings into its causes. Along their exodus, many of the most idealistic refugees founded towns such as Nicodemus, Kansas and Boley, Oklahoma – both now National Parks.

During the nadir of race relations, the all black towns were a stratagem within the overall African American historical project, as Rousseau put it in The Second Discourse, “to live and die free.” Allensworth, California was among the most sophisticated of utopian outposts, an intentional community, a visible sign of African American ingenuity in response to a country, as W.E.B. Dubois put it in 1903 in The Souls of Black Folks, “haunted bythe ghost of an untrue dream” of white supremacy.

“The Negroes of this town…are prosperous, happy and contented.”

“The Negroes of this town…are prosperous, happy and contented.”

Charles Alexander, The Battles and Victories of Col. Allen Allensworth , 1914 Allensworth was founded on August 3, 1908 by a distinguished group of Los Angeles residents, educator William Payne, Rev. W.H. Peck, miner J.W. Palmer, real estate agent Harry Mitchell, led by Col. Allen Allensworth. Allensworth was a national figure, perhaps the Colin Powell of his day. Born into slavery, after three attempts, he fled behind Union lines during the Civil War. Spent years in the U.S. Navy, in various businesses with his brother, became educated and ordained a Baptist minister. Already renowned, he successfully applied for one of the first commissions as a U.S. Army Chaplain after the Civil War, and was appointed by President Grover Cleveland in 1886 as Chaplain of the all-black 24th Infantry, which, along with the 25th Infantry and 9th and 10th Calvary comprised the Buffalo Soldiers.

After his remarkable Army career, Allensworth moved to California to realize a long held dream. He and his colleagues incorporated with the State Attorney General’s office and began to sell lots to Negro families who shared the values of “industry and thrift.” From the beginning, Allensworth’s goals of civic empowerment were clear. The Los Angeles Times reported Col. Allensworth’s remarks for the new town’s opening ceremonies. “The chief object of this community will be to aid in settling some of the vast problems now before this country…A large number of our fellow countrymen have been taught for generations that the Negro is incapable of the highest development of citizenship…If we expect to be given due credit for our efforts and achievements…people of our race must be in a community where the responsibilities of its municipal government are upon them and them alone.”

After his remarkable Army career, Allensworth moved to California to realize a long held dream. He and his colleagues incorporated with the State Attorney General’s office and began to sell lots to Negro families who shared the values of “industry and thrift.” From the beginning, Allensworth’s goals of civic empowerment were clear. The Los Angeles Times reported Col. Allensworth’s remarks for the new town’s opening ceremonies. “The chief object of this community will be to aid in settling some of the vast problems now before this country…A large number of our fellow countrymen have been taught for generations that the Negro is incapable of the highest development of citizenship…If we expect to be given due credit for our efforts and achievements…people of our race must be in a community where the responsibilities of its municipal government are upon them and them alone.”

By 1914, the settlement boasted 400 residents on 900 acres valued at $112,500. Allensworth had a debating society; symphony orchestra; the West Coast’s version of the Fisk Jubilee Singers; Women’s Improvement League; the first branch of the Tulare County Public Library; the first all-black school district in the state; and voters elected California’s first black constable and justice of the peace. There were three stores, one of them the general store for the region; a Baptist Church; a one-room schoolhouse, a lending library, stocked when the Col. donated his private book collection. Allensworth had its own hotel, and its own water company, for years it was the main loading depot along the Atchinson, Topeka & Santa Fe railway between San Francisco and Los Angeles. Historical documents and the recollections of residents show that Allensworth was very much a part of life in Tulare County, and in the larger imagination; Los Angeles observers kept track of its progress; the black press, as well.

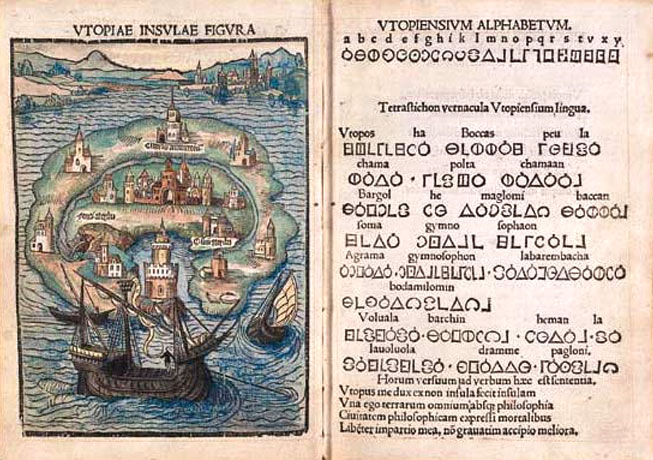

For many reasons common to experimental societies, Allensworth declined. Now, a State Historic Park, you can visit the restored residence of Col. and Mrs. Josephine Allensworth, sit at a desk in the schoolhouse, peer into the renovated black smith shop, well-tended home interiors, see remnants of the experimental garden, the street signs named for Paul Laurence Dunbar, Harriet Beecher Stowe. Gaze upon the earnest faces of the founders of this place in photo portraits in the Visitor’s Center. As you depart, the fierce sun settling red pools upon the mountain tops, you may have tears in your eyes. And the conviction that these black Utopians desired above all to live as Thomas More recommended, in a society “well and wisely governed.”

For many reasons common to experimental societies, Allensworth declined. Now, a State Historic Park, you can visit the restored residence of Col. and Mrs. Josephine Allensworth, sit at a desk in the schoolhouse, peer into the renovated black smith shop, well-tended home interiors, see remnants of the experimental garden, the street signs named for Paul Laurence Dunbar, Harriet Beecher Stowe. Gaze upon the earnest faces of the founders of this place in photo portraits in the Visitor’s Center. As you depart, the fierce sun settling red pools upon the mountain tops, you may have tears in your eyes. And the conviction that these black Utopians desired above all to live as Thomas More recommended, in a society “well and wisely governed.”

Photo-Comment from Sandra McNeill:

“Cool article on Allensworth. Here’s Niazayre and Zayden Lee with their cousins at a week-long “Descendant’s Camp” in Nicodemus, KS last summer. They had a blast learning about their genealogy (they can trace straight back to one of the founding families), as well as learning about agriculture, many great Kansas University athletes who are their relatives, fishing, and just how HOT central Kansas is in mid-summer.

An inspiring portrait of the movement and drive behind the founding of Allensworth. I hope you turn this into a book, Ms. Anderson!

This is fascinating. I had no idea about the independent black town movement. Thanks so much for sharing!!

I had the pleasure of visiting the town years ago with my family an was amazed by the history of Allensworth and the independance of the township,I thank you for perserving this for future generations.

Cool beans

I really enjoyed your article