One of the most inspiring episodes of popular uprising to me was the Paris Commune, a brief but visionary period of communal governance of the city of Paris by its people.

One of the most inspiring episodes of popular uprising to me was the Paris Commune, a brief but visionary period of communal governance of the city of Paris by its people.

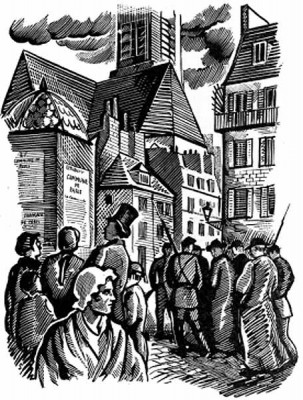

The commune was established in March 1871, and arose in large part out of the devastation and anger of the people of Paris in the aftermath of France’s defeat in Franco-Prussian War. During the war, poor and working class Parisians had fought the Prussian army in defense of the French republic. Many felt they had been betrayed by their generals, some of whom supported a monarchist form of government and fought only half-heartedly for the republic. On a broader level, the gap between rich and poor in Paris had been growing for decades, and the city had become increasingly segregated along income lines. 30 years earlier, another set of urban insurrections, culminating in 1848, led the famous urban architect Baron Haussman to embark on total reorganization of the city aimed at controlling its populace and preventing street rebellions. By 1871, Haussmann’s lavish remodeling of Paris was contrasted starkly by the destitution of the city’s urban poor. Another critical piece of the context for the Paris Commune was that Parisians did not have their own municipal government. Much the same as Washington D.C. today, Paris was the national seat of power and it was France’s national government, rather than a city council, that exercised control over local affairs in the city.

According to Arthur Arnould, an anarchist member of the communal council and a member of the International Worker’s Association:

“During [the Commune’s] short reign, not a single man, woman, child, or old person was hungry, or cold, or homeless… It was amazing to see how with only tiny resources, this government not only fought a horrible war for two months, but chased famine from the hearths of the huge population which had had no work for a year. That was one of the miracles of a true democracy.”

The Paris Commune started when, in mid-March of 1871, hundreds of Parisians faced off against the French Army that had been sent to reclaim possession of canons leftover from the war. When the soldiers on duty defected and allowed the people to capture and kill their general, the national government fled to Versailles, leaving the people of Paris to call for immediate elections of a new local government on March 26th. Two days later, The Paris Commune was declared.

One of the greatest accomplishments of the Paris Commune was its formation of a radical and participatory democracy. As one participant declared at one of the commune’s early assemblies, “the people are tired of saviors!” The government of Commune was based on a delegate system of governance, in which 20 districts elected delegates who would represent them on the Communal Council. Unlike representative democracy in which elected officials are confirmed by their constituents only once every 2 to 4 years and can act as they wish in the interim, the delegates on the Communal Council conferred with their districts on every major issue and were bound to represent their will of their communities on the council. Failure to accurately represent their districts made communal delegates subject to immediate recall, and voter assemblies could be called by a simple majority at any time in order to hold their delegates accountable. Aside from representation on the communal council, districts were largely autonomous, and there was no set prescription for how a district should be organized or run. Districts were often organized very differently from each other, but all served as the primary mechanism of implementation of Commune decisions & policies. It was at this most local level that the work of Communal government was done and, simultaneously, that the government itself was held accountable.

One of the greatest accomplishments of the Paris Commune was its formation of a radical and participatory democracy. As one participant declared at one of the commune’s early assemblies, “the people are tired of saviors!” The government of Commune was based on a delegate system of governance, in which 20 districts elected delegates who would represent them on the Communal Council. Unlike representative democracy in which elected officials are confirmed by their constituents only once every 2 to 4 years and can act as they wish in the interim, the delegates on the Communal Council conferred with their districts on every major issue and were bound to represent their will of their communities on the council. Failure to accurately represent their districts made communal delegates subject to immediate recall, and voter assemblies could be called by a simple majority at any time in order to hold their delegates accountable. Aside from representation on the communal council, districts were largely autonomous, and there was no set prescription for how a district should be organized or run. Districts were often organized very differently from each other, but all served as the primary mechanism of implementation of Commune decisions & policies. It was at this most local level that the work of Communal government was done and, simultaneously, that the government itself was held accountable.

In its reorganization of social and economic relations, the Paris Commune did not follow ideological prescriptions. In terms of economics, their goal was not to abolish private property or immediately socialize the means of production, but rather to ensure that their use and the use of all resources went to meeting the needs of the people. Hotels were taken over to house the mass of refugees that had been created by the Prussian incursion into Paris and its surrounding suburbs. Canteens were set up to feed the people, while wood, coal, and other necessities were distributed free to those in poverty or at low prices to others. Workshops whose owners had fled to Versailles along with government elites would become collectivized and put in the hands of the workers. The communal government also rewrote many large contracts in order to establish a minimum wage and often included a provision that payment to contractors should, whenever possible, be made not to the employers but to workers cooperatives. The council members established low wages for themselves to prevent against the bourgeois allegiances of those in national government, and to ensure that workers would continue to work.

The people of the Paris Commune knew that liberation didn’t come only from freedom to work, live, and associate without exploitation and war, but that culture and education both played enormous roles in the fabric of a free society. Among the nine Commissions of the Communal council was a new Artists Federation, overseen by a council of 47 artists and crafts people. The Federation aimed to break down the distinction between fine arts and applied arts and organized numerous exhibitions that included both forms of craft. A theater group called The Comedie Francaise performed every day for free, and the opera houses and concert halls, now collectivized, were also home to constant cultural activity and performances.

Because the Church played such a central role in France’s education system, the commune took over all church property and intended it to be reused for the purposes of a free, secular education for all children up to the age of 12. Upon the opening of a boys school during the Commune’s brief governance, the speaker told the children,

“The Commune, my little friends, wants all children to be healthy in mind and body, generous, lovers of truth and justice, and to ardently desire equality in their duties as well as their rights.

”Finally, each of the 20 districts had a chapter of the Women’s Union. Women played a huge leadership role in the political and social life of commune, and fighting patriarchy became a central goal of their work. The Women’s Union was politically and financially supported by the Labor Commission, and, at its height, had between 3 and 4 thousand women attending its assemblies. Their demands of women’s emancipation were inextricably tied to their demands as workers, which linked material conditions with spiritual and emotional life. Two of their demands read:

1. A variety of work in each trade – continually repeated manual movement damages both mind and body.

2. A reduction in working hours – physical exhaustion inevitably destroys man’s spiritual qualities.

One of the things I find most powerful about the Paris Commune is that it is a shining example of working people rising up to take control of their communities and institute a democratic governance structures and forms of social and economic organization that met their needs.

So often through out history, our models for revolution are cases where the goal was to seize state power, and so often these models simply replaced one form of domination by the few over the many with another. In Paris, the communards aim was not to wield power and control over a nation, but to reclaim control of a local community from an unaccountable national government. By all historical accounts, the communards did a remarkable job of running their city, and many who were present said the streets of Paris were cleaner and safer under the Commune than ever before.

So often through out history, our models for revolution are cases where the goal was to seize state power, and so often these models simply replaced one form of domination by the few over the many with another. In Paris, the communards aim was not to wield power and control over a nation, but to reclaim control of a local community from an unaccountable national government. By all historical accounts, the communards did a remarkable job of running their city, and many who were present said the streets of Paris were cleaner and safer under the Commune than ever before.

Tragically, the strength of the communards was matched only by the vicious brutality with which the French government entered Paris and destroyed the Commune barely more than two months after its inception, executing anyone associated with the Communal regime and indiscriminately killing tens of thousands of Parisians. In one week, more than 30,000 were killed. Ironically, those final bloody days inspired what would become the global anthem of working class movements in the 150 years since. The Internationale has been translated into hundreds of languages and has galvanized workers, students, and popular movements around the world.

Ginny Browne is a masters student at UCLA’s Department of Urban Planning and a member of a radio collective called Possibilities in Action. This piece originally aired on one of their recent shows on KFPK 90.7 fm.

“so often these models simply replaced one form of domination by the few over the many with another.” I do stress that point… Indeed Communards were really careful to rethink power…