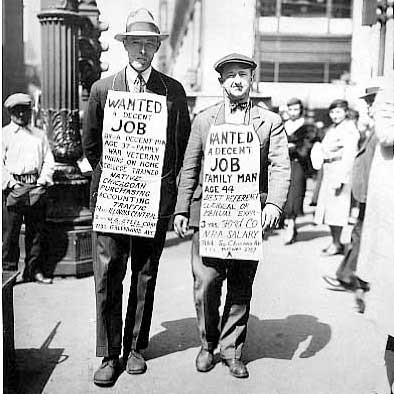

When the stock market crashed in October 1929, a decade long economic downfall, known as the Great Depression, ensued in the United States and quickly spread across the world. In the U.S. a quarter of the population was out of work and shantytowns known as “hoovervilles” (after President Hoover, blamed for the crisis) proliferated across the country. Factories went idle, while farmers were producing goods they could not sell. This was made worse by years of severe drought and dust storms that forced farmers off their lands. Tens of thousands of families migrated from farms primarily in Oklahoma and Texas to California, only to find more deprivation brought on by the Great Depression. The images of this time are well known: scores of people lining up for work, bread and soup, and the haggard faces of the “Okies” depicted in Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath.

Dorothea Lange/Library of Congress

Source: Library of Congress

Bread line (Source Library of Congress)

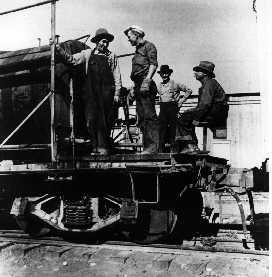

What is forgotten about this history however, is the largest unemployment movement in the history of the United States that emerged as a bottom-up response to the Great Depression. This movement, which came to be known as the Self-Help Cooperative Movement, originated in 1932 when unemployed workers from Compton in Los Angeles, reached out to farmers on the outskirts of the city, to provide their labor in exchange for food. At the time, crops were left to rot in fields, as farmers could not afford to pay workers, and people went hungry.

Jan 15, 1933: After working in the fields, self-help cooperative members collect their wages in vegetables. Source: Los Angeles Times

What was born out of simple and individual labor exchanges like these, eventually grew to become a mass movement across the nation, involving up to 1.3 million people across 30 states. The intended goal of the Self-Help Cooperative Movement was to provide full employment to all Americans through the creation of worker and consumer cooperatives. From farming exchanges grew a host of other activities, including shoe shops, medical services, bakeries, canning, gas and service stations, all operating on cooperative principles. The epicenter of the movement was in Los Angeles and more broadly in California. As Rachel A. Surls reports:

“At the cooperative in Santa Monica, members worked at local dairies for milk and cheese. They had an arrangement with the College of Agriculture at UCLA to tend the trees at UCLA’s experimental farm in exchange for fruit. The Huntington Park Cooperative had vegetable gardens on vacant land, harvesting more than 27,000 pounds of fresh produce in just one quarter of 1936. Typically, cooperatives were able to find vacant buildings to use at no charge for meeting places, to store their bartered goods, and to conduct business.”

Unemployed Citizens League Commissary, Santa Monica. Source countercurrents.org

Women work at the Kirkland Cooperative Cannery in July 1939. Source seattlepi.com

Delta Cooperative Farm, Hillhouse, Mississippi. June 1937. Source Dorothea Lange/Library of Congress

New bartering and currency systems also emerged to account for the flexibility in needs and skills. The Unemployed Exchange Association (UXA) started when residents of the “Pipe City” hooverville in Oakland, California, began offering home repairs to people in exchange for unwanted goods.

“They repaired these and circulated them among themselves. Soon they established a commissary and sent scouts around the city and into the surrounding farms to see what they could scavenge or exchange labor for. Within six months they had 1,500 members, and a thriving sub-economy that included a foundry and machine shop, woodshop, garage, soap factory, print shop, wood lot, ranches, and lumber mills. They rebuilt 18 trucks from scrap. At UXA’s peak it distributed 40 tons of food a week.

It all worked on a time-credit system. Each hour worked earned a hundred points; there was no hierarchy of skills, and all work paid the same. Members could use credits to buy food and other items at the commissary, medical and dental services, haircuts, and more. A council of some 45 coordinators met regularly to solve problems and discuss opportunities.”

Photos at the UXA by Dorothea Lange/Library of Congress

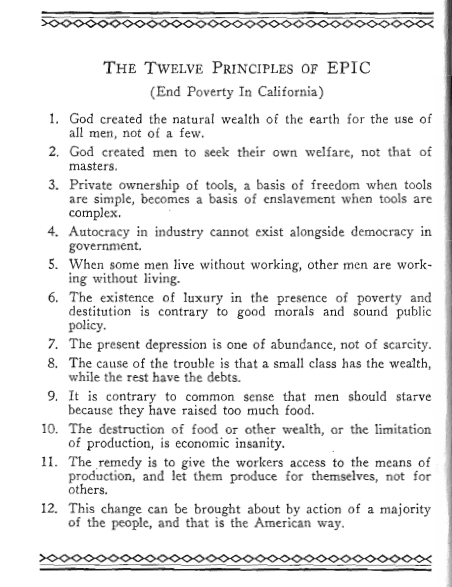

In 1934, popular socialist writer Upton Sinclair, ran for governor on a platform known as the End Poverty In California (EPIC) plan, on the back of this movement. In his “I, Governor of California, and How I Ended Poverty: A True Story of the Future”, Sinclair called for an end to unemployment by putting the unemployed to work in unused farms and factories, to be run as cooperatives. Goods were to be traded to meet people’s needs, and the state was to support cooperatives, the infirm and the elderly.

Despite benefitting from tremendous popular support, Upton Sinclair’s gubernatorial campaign ended in defeat after a long and bitter battle. While cooperatives continued to benefit from support on the ground, particularly in Los Angeles, they progressively lost political and financial support, when they came to be seen as communist endeavors. When the WPA programs began, people abandoned the co-ops for regular paychecks. The movement came to its end in 1940 when the state of California pulled its financial aid to the remaining cooperatives.

The Self-Help Cooperative Movement is largely credited for influencing New Deal programs and other state-level socialist legislation passed through in the 1930s and 1940s. Credit unions, which remain today, were also born of this movement. Today, with the resurgence of cooperatives and the rise of the so-called “sharing economy”, there are important lessons to be learned from this period in history when people created a true “sharing economy” based on reciprocity, ability and need.

For more on this movement, check out Dr. Pasha Abdurrahman’s PhD thesis on the subject here.

I see you don’t monetize your blog, don’t waste your traffic, you can earn additional bucks every month.

You can use the best adsense alternative for any type

of website (they approve all websites), for more info simply search in gooogle: boorfe’s tips monetize your website

This text is worth everyone’s attention. Where

can I find out more?

https://www.countercurrents.org/curl030510.htm

https://www.yesmagazine.org/issue/issues-5000-years-of-empire/2018/09/14/what-history-books-left-out-about-depression-era-co-ops/