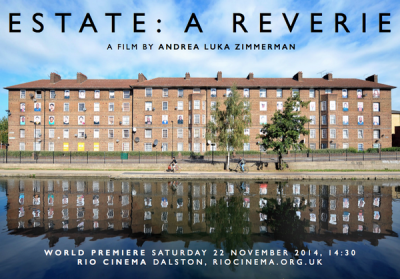

Once upon a time I lived in Bow, and out for a long wander up the Regent’s canal one day, I saw this:

A wondrous thing. I had passed other estates with windows boarded up yet signs that people still clearly lived in them. This left me both angered and confused, as housing is in such short supply for us, and this is our housing standing empty. These are homes that people live in and love in the midst of desolation. Here I could tell someone was fighting back, ensuring they were visible and not simply to be silently swept away.

I met Andrea Luka Zimmerman and Lasse Johannson (part of Fugitive Images, those who had put up these pictures with fellow residents) a few months later, the three of us on a panel put together by This is Not a Gateway at the Tate Modern (the Tate Modern! I called home, ever so proud).

This photo installation, I am here, was only the first part of a longer exploration of the process of decanting an estate against its resident’s wishes. This, a protest against the estate’s abandonment in preparation for regeneration. It sat alongside endless meetings, letters, petitions, protests, lobbies to preserve and improve the housing for those who lived there and loved it.

The second was the book, Estate, a combination of personal essays, photographs, and political-economic contextualization. I loved it. You can buy it here, from Myrdle Court Press.

The second was the book, Estate, a combination of personal essays, photographs, and political-economic contextualization. I loved it. You can buy it here, from Myrdle Court Press.

The film Estate: A Reverie is the third, and perhaps the most powerful of the three. especially as the Haggerston Estate is now gone, demolished, dust. I finally got to see it as part of the Open City Doc Festival.

I had seen various versions of the film over the years — in snippets, and bits and pieces. A work in progress always. But I wasn’t prepared for the full feature.

(After going through the foreclosure with my mum only a year ago, a replay of losing the house we built with our own hands when I was a teenager, I feel I have lost a home twice, and this drew upon all the neverending grief and anger that such experiences leave inside of you. I don’t know if anyone else dripped tears throughout.)

Inspiring and heartbreaking both, it does two things wondrously well.

It shows the residents as they were and as no one else will ever show them — neighbours getting to know each other, the ways they had chosen to decorate their rooms, children playing and growing up, a father and daughter being forced to move, the elderly over time as they grew sicker and sicker. It contains the most honest view of Parkinson’s I have ever seen. It brings the people of Haggerston Estate into your heart and they will never leave it. It doesn’t do this with a bright and clinical gaze, but with the warm compassion of someone who has shared space with them for fifteen years. A gaze that sees people as they are for good and bad, and thus can love them truly.

Estate allows you the signal honour of sharing in a real way the suffering the lack of repairs has caused and the pain of losing of this community. Something planners and housing managers and city officials somehow never understand.

This film could only have been made by someone who had lived there, fought for it, loved it.

That is why it captures so beautifully the magic that also happened here. The radical insurgency of this space. Slated for regeneration, the council stopped caring what people did here. Relaxed the patronising and controlling sets of rules that controlled behaviour. You hear a woman recount a story of her grandfather moved here from the slums when the estate first opened. Removed from his home and patch of ground and his animals. When they tried to force him to get rid of his dog too, he gassed both of them in the apartment.

Those days are gone, this film is full of dogs. It is full of colour. It is full of life and song and rebellion. People didn’t run riot in this ‘problem’ estate, they painted logs and made seats. They painted goal posts on the wall for the next-door kids, they planted flowers and vegetables. They had barbeques and built a fire pit and sang songs to welcome in the New Year. They helped each other. They told stories.

They put on regency dress and discussed and acted out Samuel Richardson’s novels, whose heroines provide the names for the estate’s buildings.

Councils never did quite figure out that poor people weren’t the enemy, and the slums weren’t their creation, did they. The film does not forget to situate this place in context, to plant it firmly in the history of this neighbourhood over time and through the complexities of government interventions.

But oh, the things people on estates can build when left alone to come together as a community.

There is so much more to say, but you need to watch it. I thought I’d end with just a few rough notes from the wonderful Q&A that followed with my tocaya:

She highlighted that this was a film of all the things unseen, meant to explore what it meant to lose the place after so many years fighting to improve it. It emerged from that struggle, the experiences they had there, but also the feeling that they had to do something after the financial crash. Seeing the posters go up everywhere about benefit fraud with slogans like ‘we are coming to get you’ as though people on benefits were to blame for everything. The strong feeling that something must be done to challenge this image production that blamed everything on the poor.

This was always a collective effort.

She talked too about the transition period that stood out so clearly for me in the film, a period of so many years where the council’s neglect meant they could do anything they wanted, a time when people were able to take the space and decorate it as they wanted, create in it what they wanted. As a result it became a magical place.

There was a question about why this film didn’t show the struggle, the fight to improve it and keep Haggerston Estate. The fight against gentrification and regeneration of which it clearly forms a part.

Hard choices were made on this, footage exists of everything, but there are so many films of struggle, it is something we understand (even if we don’t yet know how to win — but that is my own aside). She chose instead to show the reality of people’s lives, explore not just what the estate and its loss meant to them, but what they were able to create there when allowed some freedom for creation.

(In a previous cut, I remember seeing people come back to the estate who had already moved on, bursting into floods of tears at seeing their old flats, torn in half between memories of all the frustrations of living somewhere in such terrible conditions but also all of the memories that still made that space a home. It was so powerful but Andrea is right, it did not fit here).

She talked about the architecture. These concrete and brick modernist buildings are vilified now, yet in their ‘passages in the sky’ you have to meet your neighbours, you see them every day, you say hello. New buildings are secure by design, you never see anyone, community cannot grow and people are lonely in them.

Something else we are losing. We still have a great deal of public space, it is important in this country, but home is still seen as private, insular and becoming more and more so. It’s an interesting observation. Early estates were built to try and help create community, with multiple shared living spaces — perhaps not public space but community space. That is something that is disappearing, and surely we are losing something with it.

There is so much to think about here, the film so rich it will reward reviewing. Go see it. There is no mainstream distributor as you can imagine, but anything you can do to help pass the word would be much appreciated, and I’m sure we could help you arrange a screening.

Estate, a Reverie, 83mins, 2015 (Trailer) from Andrea Luka Zimmerman on Vimeo.

One Comment