If you live in Chicago Tax Increment Financing (TIF) likely impacts you in some way or another. TIFs cover about a third of Chicago’s land area. Yet to many of us TIF is elusive. We either don’t know it exists, or steer clear of this complicated-sounding financing mechanism. However, the nefarious use of TIF requires us all to take a serious look at what’s going on and figure out how to change it.

If you live in Chicago Tax Increment Financing (TIF) likely impacts you in some way or another. TIFs cover about a third of Chicago’s land area. Yet to many of us TIF is elusive. We either don’t know it exists, or steer clear of this complicated-sounding financing mechanism. However, the nefarious use of TIF requires us all to take a serious look at what’s going on and figure out how to change it.

First off, readers who are unfamiliar with TIF should get acquainted with what it is and does.

TIF is a state authorized economic development tool meant to combat blight, or disinvestment. Blight itself is based on the state’s definition (written into the law authorizing TIF), including things like age of structures or building code violations. Sometimes this can be more clearly measured or observed (as with building code violations), other times, not so much—things like dust on the window sills and dirty dishes in the sink have been used as blighting factors in buildings. The basic idea here though is that TIF will act as a strategic financial intervention in blighted areas that otherwise wouldn’t attract investment.

In an area with enough blight, a TIF district is designated, which leads us to the issue of financing.

TIF is funded through taxes on property value. In short, TIF uses the expected growth in property value to fund development projects in the present. It does this by freezing property value in the area for its lifespan of 23 years. Any increase in property value during that time (in theory caused by TIF-funded development) is taxed and put in the TIF fund, which is kept separate from the normal taxing bodies.

A common complaint then is that the separate TIF fund takes from schools, parks, and other taxing bodies, which we depend on for vital services. TIF advocates counter by arguing that TIF funds development projects that benefit residents in the meantime, which increases the tax base as a whole—increasing our quality of services at the end of the 23 years.

So what’s the fuss about then? In theory, it sounds like TIF pays for itself and benefits everyone.

The issue lies in the use of TIF: who controls it and what projects they fund. This is a fundamental problem considering Chicago TIF’s notorious lack of transparency. This has allowed TIF to be very much at the disposal of the rich and well-connected, who use it as a vehicle to fund projects in their best interest—at the expense of the rest of us.

In mid-November of 2012, the Chicago Teachers Union made this exact point. They filled the lobby of the Hyatt Chicago Magnificent Mile in protest of Chicago billionaire, part-owner of Hyatt Hotels, and then Chicago Public School (CPS) board member Penny Pritzker for being awarded $5.2 million in TIF funds for a Hyde Park Hotel. During the protest, one CTU member summed up the unequal use of TIF succinctly, yelling: We have fat cats like Penny Pritzker who take money from our schools and put them into the Hyatt.

TIF has far strayed from its original intent to help blighted areas.

And what better way to illustrate that than with Chicago schools. We often hear of under-performing, under-utilized, and dilapidated public schools. Considering that 299 (or 43% of) Chicago schools are in TIF districts one would imagine TIF can do something to help.

So far, it hasn’t. In fact, TIF has only contributed to the unequal distribution of resources within the school system, depleting public neighborhood schools of resources and giving school reformers the justification they need to put public neighborhood schools on the chopping block.

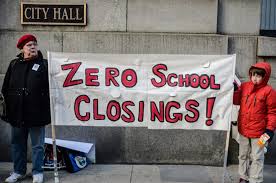

This is why 54% (or 70 schools) of the proposed 129 school closures are located in TIF districts (Figure 1). (This list has since been cut to 54 schools—still the greatest number of school closures in US history—however, the old list is relevant for the purpose of this piece.)

This is why 54% (or 70 schools) of the proposed 129 school closures are located in TIF districts (Figure 1). (This list has since been cut to 54 schools—still the greatest number of school closures in US history—however, the old list is relevant for the purpose of this piece.)

The key issue here is the types of schools TIF funds. There are a variety of Chicago schools, which a CReATE brief breaks down into two helpful categories: neighborhood schools and exclusive schools. Neighborhood schools are fully public, open enrollment schools. Exclusive schools are part-public, part-private, or fully private schools with various barriers to entry, like an entrance exam or an interview process.

Building exclusive schools is an education reform strategy starting in the 1990s, which has been criticized for unevenly investing money and resources into the exclusive schools at the expense of neighborhood schools. The strategy, however, plays to the interests of urban elite who see this version of school reform as a means bolster market activity and act as an anchor for young professionals in the city.

And lo and behold, it turns out that TIF worked as a vehicle to fund the exclusive school strategy, which benefits the rich and well-connected Chicagoans who then chastise under-performing and under-utilized neighborhood public schools.

Let’s look at the numbers. Exclusive schools make up roughly 30% of all Chicago schools but received over 50% of TIF founds. Selective enrollment schools (a type of exclusive school) made up 1% of Chicago schools but received 24% of TIF funds. On the other hand, neighborhood schools, which make up roughly 69% of received 48% of TIF funds.

The depletion of funds for neighborhood public schools is striking when looking at the types of schools in TIF districts that were pegged to close versus those that were not. While, neighborhood schools made up 63% of all the schools in TIF districts, they made up 93% of the 70 schools in TIFs slated to close.

Thus, the money for schools was out there (in the form of TIF funds) it was just used to fund a particular strategy of school reform that benefited urban elites by taking from working-class and poor neighborhood schools.

There are two important take-aways from this. First, TIF is contributing to inequality in our cities by taking from the 99% and aiding the 1%. Second, TIF’s unequal use is an important political issue that those of us in Chicago (not part of the 1%) can use as a cry of injustice and demand for a more equitable city.