Last week, I visited the Japanese American National Museum in Little Tokyo Los Angeles. Two tiny elderly women were standing next to a reconstructed portion of barracks from the Heart Mountain, Wyoming concentration camp (official name: Heart Mountain Relocation Center), one of 10 used to intern 110,000 Japanese-Americans citizens and Japanese immigrants in the United States during World War II. The women were pointing and describing remembered features of the barracks’ construction.

See the spaces between the wood?

They used green wood that expanded and contracted with the weather…

That’s why the tar paper was so important…

I asked the women if they had lived in Heart Mountain. “No,” one replied. “Manzanar”, the other explained. Manzanar. Remotely located 230 miles northeast of Los Angeles and infamous for its harsh desert temperatures and wind storms that cover everything and everybody with dust.

Manzanar (wikipedia)

Manzanar (wikipedia)

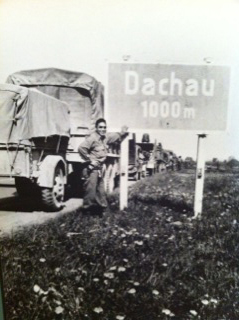

I asked more questions about what they did there, what it was like. They told me. And then one of them said quietly, “You know, of course, this could happen again.” Wanting to share, I told her about my visit, about 20 years ago, to the Dachau concentration camp, now preserved as a museum. I am Jewish, and on train to my destination, I prepared myself to receive some kind of Jewish epiphany, revelation, or at least, experience.

But that is not what happened as I moved through the exhibits. The words that appeared in my head and my heart were “This could happen again,” followed by an “aha” moment, a reverie:

This is what the Salvadorans and Guatamalens in L.A. mean when they say that friends and family were “disappeared.” This why the “conflict” in the Middle East continues and continues and continues. This was the alternative story ending to apartheid. This horror is a human thing. It has no particular color or race or time.

But humans are capable of transcendence. We also contain luminous possibilities for good, beauty, and caring for each other. This tendency is the bedrock of all social justice activists and the movements that we embrace, hoping to advance history in the direction of the light.

After I told my new Japanese-American acquaintances my Dachau story, one of them nodded and smiled. “Since you brought up Dachau”, she said, “I’ll tell you another story.” She told me that the first American soldiers to liberate the prisoners from the concentration camp were G.I.’s of the segregated, Japanese-American 522nd Field Artillery Battalion. “They weren’t supposed to be there. They didn’t have orders to do what they did. But so many of them had family at home in camps like Manzanar. They had to do something.”

While she was in Manzanar, two of her brothers were serving in the U.S. Army. Four of her companion’s brothers served as well.

Melvin Hamamoto (Japanese-American National Museum)

Melvin Hamamoto (Japanese-American National Museum)

She went on to tell me how some of the prisoners first reacted to their liberators fearful that they were now prisoners of the Japanese. We laughed. We could laugh across the oceans of time that separated the circumstances of our meeting from those events.

At the same time that my museum friends were interned in Manzanar, my mother, who would have been their age, lived in a different kind of camp on the other side of the country, a refugee camp at Fort Ontario in Oswego, New York, preserved today as the Safe Haven museum. She was one of the the 982 Jewish refugees who sailed from Italy to the U.S. as “guests” of President Franklin D. Roosevelt –– guests who were asked in advance to pledge in writing that they would return home once the war was over. The museum website recounts the difficult journey, elation at the sight of the statue of liberty, and the somber approach to the camp:

A train, a reminder of the ones bound for Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, carried the refugees north to Oswego and a decommissioned military base at Fort Ontario. Barbed wire fences and military personnel greeted them at their new home. Refugee Walter Greenberg comments, “I felt deceived. I felt that I should have been free. I mean, I felt wonderful. I had doctors. I had nurses. I had food. I came to school. Oswegonians were very kind… What good is it to have all the amenities of life if one still isn’t free?”

The Japanese American Museum is across the street from the original Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist temple where Los Angeles Japanese Americans were boarded onto buses bound for the camps over 60 years ago. My conversation may have been by chance, but such conversations are institutionalized possibilities in the museum, where many of the volunteer docents are veterans of the camps. As I left the two women to view the exhibits, docent “Babe” Karasawa, approached me and asked if I had any questions. Babe had been interned in Poston, Arizona during the war, a place where Japanese-American prisoners became forced labor to build irrigation and other infrastructure for the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ projected relocation of Hopi and Navajo tribes. A camp for building a camp.

Babe (yes, his nickname is connected to baseball and Babe Ruth) asked if I was Jewish and then directed me to an exhibit case containing the book Year’s of Infamy: The Untold Story of America’s Concentration Camps, which helped fuel the Japanese-American reparations movement. The author, Michi Nishiura Weglyn, was interned with Babe’s wife at the Gila River camp in Arizona and married to Walter Weglyn, a Dutch Jewish Refugee, one of the few children from his hometown who did not die in the Nazi Holocaust. It was Walter who encouraged Michi to call the “relocation camps” by their true name: concentration camps. To Babe, and to the museum, this naming is an essential part of reclaiming history, reclaiming Little Tokyo, and making justice new again. The museum takes great care in defining the term:

America’s concentration camps are clearly distinguishable from Nazi Germany’s torture and death camps. Six million Jews and many others were slaughtered in the Holocaust.

Despite the differences, all concentration camps have one thing in common: people in power remove a minority group from the general population and the rest of society lets it happen.

As historical themes about race and hate and exclusion re-emerge today, what actions do we take to ensure that “it” doesn’t happen again? Is it possible for the “general population” to imagine a world where reducing inequality, collectively producing place, and restoring and healing our cities and ourselves is our shared project? Our policy.

It is not entirely a coincidence that the initial convening of the Right to the City Alliance in the U.S. was held at the Little Tokyo Cultural Center, a few blocks from the museum. A young organizer from the Little Tokyo Service Center, two or three generations apart from my museum guides, told us some history about where we were. We learned about redevelopment and displacement, about the struggles that produced the building, the struggles that continue. We identified with the stories and the frame of spatial (in)justice that we shared across our diverse organizations and regions

As I write, tens of thousands of people are demonstrating in cities across France against a government law and order crackdown that has targeted Roma gypsies for expulsion from the country. Some journalists and politicians have compared the images of Roma families being “rounded up” onto buses to “Vichy France’s round-up of Jews” and thousands of gypsies, many of whom were killed in concentration camps. These memories of (in)justice are alive in the spaces where opposition party leaders are marching alongside Roma migrants whose camp has just been bulldozed by the authorities.

In the in the U.S. activists in cities across the country are taking to the streets to protest Arizona’s AB 1070, the nation’s strictest anti-immigration law in decades. Marching in the shadow of the history of the Poston and Gila River concentration camps’, many suffer arrests and political retaliation in order to protect the side of right and the rights of all.

Yesterday I was sitting in the park outside the Downtown Library, (one of the city’s last great free spaces) reading a book, with my back turned to my seat-mate, a nice homeless man, who got up and came over to me to say, “Sorry, but I was reading the back of your shirt. That’s deep, man. So, deep. Its so true.” He laughed with his new awareness and I laughed with him. Then he returned to his sitting place.

The words on the back of my (SmartMeme) t-shirt say:

The problem is not changing people’s consciousness – or what’s in their heads – but the political, economic, institutional regime of the production of truth.

Michel Foucault